One of my different hats at work is Jira support. As part of that, we provide advice to teams on how to best use Jira, and as a result I’ve seen Jira being used by different teams at various adoption levels and with various success. Issue tracking is a funny development practice — anyone who has used it becomes an expert in it, and there are all sorts of ways teams (mis)use it to the point that Jira has become a four letter word. The largest benefit to using Jira is that it’s flexible and powerful. But the largest problem with using Jira is that it’s flexible and powerful. When you give a demo to a team who is brand new to the concept of issue tracking, it’s easy to get into the weeds really quickly by talking about what you could do in Jira with all the bells and whistles. Add in a mandate from above that “thou mustest useth Jira” and my job in expanding good practice in issue tracking and planning becomes difficult because I’ve got a bunch of new teams lead by well meaning pseudoexperts.

In my experience (and not just with issue tracking), it’s best to start people out simply and guide them through continual improvements as they learn. With Jira specifically, I’ve noticed a pattern in the stages a team goes through in adopting Jira for planning and tracking. These stages are characterized by problems, which I outline below with symptoms and ways to solve the problems. And while I’ll mostly talk about Jira (because that’s what I’m most familiar with) the ideas apply to other issue tracking and planning tools, though the names of the features might be different.

Problem 1: “We don’t know what we need to do”

We can call this stage 0 because the team hasn’t adopted anything for issue tracking. They’re starting out, don’t know how to get started, and probably mispronounce Jira (personal pet peeve: it’s jEER-a, not jEYE-ra).

Symptoms

- Team members don’t know who’s working on what.

- Tasks are frequently forgotten or requirements misplaced.

- There are many emails from your manager asking “what’s the state of this?”

- Team members independently manage their own work and don’t collaborate.

- Task details and requirements are contained in personal stores or scattered in different places (email, My Documents, spreadsheets, whiteboards, sticky notes, random text files, shared word documents, team members’ heads, and yes, even multiple Jira projects).

- Your manager runs around to everyone’s desk every day to get a handle on what the team is working on. Or worse: requires periodic written summaries.

Solution

The solution to this problem is to take the first step and put all tasks and requirements in one place — Jira. Establish this as a pattern, as a mantra, as your email signature: “anything that needs to be done, put it in Jira!” While you’ll be tempted to use every feature in Jira right away, I recommend to just keep things simple at the start. Create a default project, nothing fancy, and use the default notifications. Don’t overthink it, just jump in and start using it!

There are, of course, some things to keep in mind, but they’re more about communication and clarity rather than features and workflow. Keep the team’s workflow simple to let them adjust to putting everything in one place. Here’s a checklist for the team in this first stage:

- Add a short but meaningful summary for an issue.

- Put enough details in the description that someone else would know what the task is and how to complete it, but no more.

- Use comments to expand or discuss the issue. Everything related to finishing the issue should stay with the issue.

- When you start working on an issue, assign it to yourself so someone else doesn’t do the same task.

- When you’re finished, resolve the issue.

- Once an issue is resolved, keep it resolved. Open a new issue for related changes.

As with anything, common sense should prevail. These are guidelines — if a circumstance makes the guidelines difficult to work with, then adjust. The goal of this stage is to get the team to change their work tracking behavior, and that’s difficult enough without getting trapped in process arguments.

Problem 2: “We have too much to do!”

After using Jira for awhile (and sticking to it), the team is going to have many issues in their project and may start to get overwhelmed by the sheer number.

Symptoms

- Team members jot down issue keys on sticky notes to bring to meetings.

- Team meetings include delays to scroll through all the issues in the project in order to find out what you’re talking about.

- Your system administrators report an increase in the text based searches in your performance log.

- You have a bunch of duplicate tasks in Jira because it’s too difficult to find out if you’ve already added the task.

- Your manager starts to lose their hair or has become very, very pale.

Solution

This problem is one of visibility — the tasks are all in one place, and they’re piling up quickly, because there’s always more work to do! This is the point where you’ll want to start establishing more disciplined and detailed team processes, but make sure that the team is aware these are to help them get organized, not to monitor them. It helps to show the tools and how they’ll help, but indicate that in order for the tools to work, certain processes have to be followed. Most people will understand that connection. Take a look at Scrum and Kanban boards, dashboards, workflows, components, and filters. Each of these items could take an entire post to discuss, so use the links to find out more.

In my experience, at a minimum introduce the basic concept of a Scrum board to the team and start doing some basic planning in week long sprints. There are many, many great articles out there on Scrum, sprints, and boards so I won’t go into details. Just remember again: it’s easy to get caught up in the many benefits of all the Scrum “stuff”, but resist that temptation and keep it simple. There’s plenty of time to level up later.

In Jira, there are two parts to a scrum board: the Backlog (or planning board), and the Active Sprint board (which is really just a Kanban board). Here’s my Backlog and Kanban board for one of my projects:

The Backlog lets you organize your tasks into time boxed groups called sprints. I recommend using a week long sprint to start just to get you into the habit of using the board, but the start/end dates and duration are flexible depending on your team. Once you start the sprint (making it the active sprint) the Kanban board becomes available and shows you which issues need to be done, are in progress, and are completed. You can drag issues in between columns or update the Jira issue. If you have an extra monitor, post the Kanban board in the team space — it’s a nice visualization and starts good team discussion. The Scrum and Kanban boards are highly customizable. When you find a few minutes, try playing with some of the visualization options to adjust the card views, colors, headings, and other board options.

Finally, update your checklist for the team:

- On Monday morning as a team:

- Review the Backlog and create a sprint for the week.

- Considering workload capability of the team that week add issues to the sprint.

- Assign all issues to specific team members.

- Start the sprint.

- During the sprint: assign yourself a task, set the task to In Progress while you’re working on it, and then Resolve it when you’re finished.

- Review the Kanban board daily to keep team members accountable. If issues aren’t moving, ask the assignee why.

- On Friday afternoon, review the work from the week, close the sprint, and celebrate the tasks done!

Problem 3: “We (still) have too much to do!”

Boards are good for visualizing and organizing work, but at this point teams will start vocalizing problems around planning.

Symptoms

- Team members are consistently under- or over- estimating the number of issues they can put in a sprint each week.

- There’s a lot of work “In Progress” but nothing seems to be “Done”.

- Issues have different levels of complexity. Some issues might take a month and others an hour, but there’s no way to differentiate them.

- You’re unable to provide a reasonable guess for when a task will be completed.

- You know what you need to do, but have no idea how long it will take to do everything.

- Your manager starts singing the praises of Microsoft Project again.

Solution

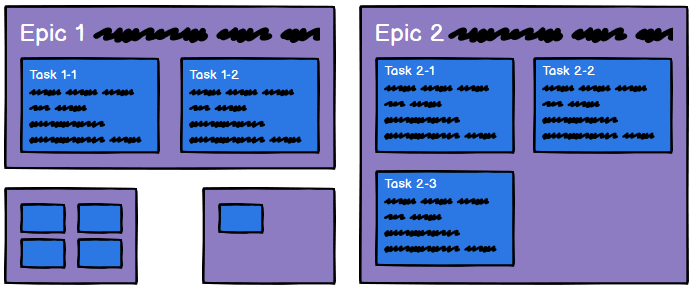

This problem is about planning, a word that techies, um, aren’t fond of. As a programmer who (gasp!) likes planning, I don’t understand why there’s such a push back to it — I want to know how long something will take and how much work it’ll be because it makes managers get off my back happy and lets me focus on getting stuff done. Plus, it’s like a programming problem — you take a larger task and use encapsulation, composition, and other patterns to break it down into smaller, easier to implement chunks. In Jira, introduce your team to epics, stories, and tasks, estimates, versions, priorities, and due dates. At a minimum, introduce task breakdown into epics and child issues, and get in the habit of estimating.

Task breakdown is an art-form. It’s hard to provide specific rules and is more of a gut feel once you have enough experience doing it. You can approach it from top-down (start with epics and add issues) or bottom-up (create all your tasks and then group them into epics). But basically, an epic is a larger bucket of work that contains issues (a has-a relationship). When is something an epic, when is something an issue, and how big do you make issues? A general rule of thumb: if something will take you longer than a morning or day to complete, then it’s too large to be one issue. From there, whether you make the issue an epic with detailed steps in child issues or separate the issue into two depends on the problem being solved and how you want to organize and describe the work. As I mentioned before, this is a guideline and let common sense rule in each situation.

Once you have epics and issues broken down, then make sure each issue has an estimate (or guesstimate). I’m not an adherent to story points from the agile world but I do suggest to teams to only use certain values in their estimates: 15m, 30m, 1h, 2h (half a morning), 4h (a morning), 7h/1d, 3d (half a week), 5d/1w, and 2w. That way you aren’t arguing over 30 minute exactness. Most people will be able to describe how long it will take them to work on something using these values. I also recommend that when you’re creating estimates to talk about three values: the best case, the worst case, and then the likely case. When you think about all three, it helps you to build in contingency into the estimate by the time you get to the likely case. Put the likely case in Jira.

Team members start to get nervous when you start requesting estimates because if you’re not careful it can devolve to being tied to individual performance reviews and in the worst case estimate games where you need to beg, borrow, and steal time from other issues. Estimates are just that — estimates. Life happens and estimates are almost always wrong. You get better at them over time, but they’re never perfect. Challenge team members to improve if their estimates seem unreasonable or if they are consistently way off, but in general don’t make the estimates a contract. Use them only as a guideline to help you plan. Do NOT associate these with team or individual performance, and reassure the team that the estimates are ultimately for their benefit.

Your checklist has new additions now for the team:

- Put high level tasks into Jira as epics.

- Break epics into smaller, implementable issues.

- Make sure each issue has an estimate.

Problem 4: “We don’t know what we’ve done!”

Sometimes teams become disillusioned by all the work that’s left to do. Jira is great to track work, but when it never seems to stop, it can be demotivating. It’s time to remind them of all the work they’ve done!

Symptoms

- The team’s enthusiasm goes down.

- Team members keep asking themselves “what the hell did I do last Friday?”

- Team members can’t let managers know how much time they’re actually spending on projects or issues.

- The team says more members are needed to complete work, but can’t give you concrete numbers to back it up.

- Managers stay at work until 8pm cursing Excel as they fudge numbers while creating operational plans.

Solution

Jira has really good reporting tools built into it. I recommend at this point to start experimenting with different dashboard widgets and looking at the default project reports. They’ll give a good picture of the health of your project and can be motivating for team members to visualize completed work. To help with those reports, encourage team members to add time logs to issues once they’ve completed them. Use the actual time to improve estimates (and remember the discussion about estimates from the last section).

For the project managers in the crowd, once you get the team to do estimates and log time, then you can start to pull together larger plans into roadmaps and delivery plans. Take a look at Jira Portfolio if you like things like Gantt charts, scenarios, and release dates. Portfolio (like Jira) is powerful, but adds a lot of complexity. But if you use Jira the way I’ve described so far, you’ll get most of the benefits of Portfolio for free with little extra work.

Conclusion

I have a love – love – hate relationship with Jira (mostly because I’m on a 3 week support rotation, ha!). There are definitely things it can do better, but it helps keep me organized, informs teammates of my progress, and doesn’t have a lot of added overhead once you set it up. I want other teams in my organization to use it too. Jira is powerful, but overwhelming at first. Don’t show a team everything about Jira all at once — let them adjust to features organically as problems come up. If teams have a hand in solving team problems by changing how they work with Jira, it increases the likelihood of long term adoption.

Happy Jira’ing!

Collene, I enjoyed reading this article. There are points to take away which will make my Jira-ing more effective. Will share this with my colleagues. Thanks

LikeLike

Thanks again Rajesh! I’m glad that you found the article helpful.

LikeLike