I like solving problems. Not so much the frustration and headaches that happen while deep into the thick of the problem. But nothing beats that feeling when you find the problem then fix it. Those problems where you don’t know how to do something are especially fun to figure out, though they bring an angst that programmers deal with differently. My description of this tension: “I don’t like it when the world doesn’t make sense”. I even bought the t-shirt.

We’ve got a project on the go right now where we’re evaluating three different products, and a team of us has to come up to speed really quickly not only in three toolsets but also in the problem space. It’s been interesting to watch the approaches of the team members as we all struggle to make the simplest of solutions work. I started thinking about how different people approach problem solving and how some methods work better than others and started to wonder why. To explore that, let me tell a fictional story of an eager intern, who for convenience I’ll call Arthur *.

* While inspired by actual events, the event depicted in this blog post is fictitious. Any similarity to any person living or dead is merely coincidental. Incidents, characters, dialogue, and timelines have been changed and incorporated from several events for dramatic and demonstrative purposes. **

** Don’t-cha love disclaimers? But seriously to anyone who thinks they see themselves or others in this story, Arthur DNE. This story is a combination of many (including me) newbies and interactions with them. I expect everyone will recognize a bit of themselves in Arthur and a bit of themselves in the narrator.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times

Arthur was a brand new intern with no previous work experience, eager to prove himself, and a super smart guy. He had that typical n00b enthusiasm, working on 10 different things at once, having an opinion on everything, and using every single one of the tools he’d just learned. He also had “just enough” knowledge of the topics to spout buzz words into a conversation, but when push came to shove had shallow practical application skills. I was fairly new to the working world myself, but had some not-so-small projects under my belt and had established myself on the team as a competent troubleshooter for hard problems, even winning an “award” for bug hunting at the end of summer party.

My desk was across the room from Arthur, and his intensity was distracting and draining. On the specific occasion of this story, I could tell he was struggling with a problem using an internal library while working on a new feature for one of our applications, and (having just “won” the bug hunting award after all), thought I could help. He started verbalizing the problem to me:

A: “Well, I’m trying to make it do action X in application A. There’s no way to do it, we’ll have to add something to the library to do it. So I’m reading into how to do that, can you show me where to install the SDK?”

C: “Ok, well I’ve used that library and have found it to be pretty exhaustive in terms of what it can do. What have you tried?”

A: “There’s no method called doActionX. I noticed there was something called doActionW and I remembered X and W were in the same course I took last semester, so I’ll use that. doActionW required three parameters, so I went and got all that information, and wrote a parser to take what I have for X and turned it into what W needed.”

C: “Are you sure using W will get to what your goal was? It sounds differ…”

A: “No, I’m pretty sure that’s what it’s supposed to do. The developer just named it wrong. I already added it in Bugzilla for someone to clean up. So after I got all the data in the way W needed it, I wrote the entire method to call it in my application, but it didn’t work. It should just work. The developer didn’t know what they were doing, there must be a bug in the library. While I’m thinking of that, I’ll add that to Bugzilla now too.”

C: “Wait just a minute on that…how did you find out about the doActionW method and the parameters? What do you know about it?”

A: “Something called auto complete in Eclipse. Look, you can see all of the different methods that you can do just by typing a period! That’s so helpful! There’s doActionZ, doActionB, and even doActionsWXY. Now I know exactly everything the library can do and the parameters. Everyone should know about this — I can do a lunch and learn session on Friday to show everyone this handy trick! Should I ask the front office staff to schedule it? No, I’ll just arrange it myself and just use the intranet’s event tool.”

C: “Uh, maybe hold off on the lunch and learn. So it looks like there’s JavaDoc for doActionW. What does it say?

A: “Actually we should switch to another event tool…the one we have sucks because I sent out invites for my last lunch and learn last week and no one got them.”

C: “Oh, wow, really, that’s too bad. Um, how do you know no one got them?”

A: “No one showed up.”

C: (Awkward pause) “Right. So back to the JavaDoc, can you open it up and see what doActionW is supposed to do?”

A: “That’s too long to read, I don’t have time to read it. I don’t like how they’re organized anyway. I can tell from the method name and the parameter names what it does and will just try a bunch of stuff until it works. So here’s the parser and after that is where the problem is — I googled change X to W and then copied the entire method this other guy posted ***. He must have been using an older version of Java though, so I had to update it. It mostly compiled, but used var instead of int everywhere.”

*** For more detail, the code on the website was not related at all to the task at hand. X and W were terms used in another domain, and this code was specific to that domain, not ours.

C: “Actually I think that’s JavaScript.”

A: “Whatever, same thing.”

C: “No, not rea…”

A: (Impatience) “For all intents and purposes, there’s no difference here. The parser code works.”

C: “Well, parsers can be tricky. What tests did you use to make sure it is working as you expect?”

A: (Silence, confused look) “My program got passed that line, so of course it worked. And the guy online proved it with a bunch of performance tests. There was a comment that it worked for someone else too. I just need to get it to do W! I probably have to change a bunch of the JVM settings so the code is compatible with my version of Java. One of the other comments said once they updated a video driver setting it worked.”

C: “Ok, well look, I’ll admit I’m a bit lost because I thought we were trying to do X? Maybe you can take me back to application A and show me what happens when you try to run your new feature?”

A: “Yeah, most people find implementing this library can get complex really quickly, but I have a lot of related experience in the area. I can explain it to you sometime.”

C: “Um, thanks.”

A: (Starts up application A) “See, crash, nothing popped up on the screen or anything. I don’t understand why it didn’t work, X is just a simple, easy task to do and the library should do it out of the box. This entire library isn’t any good, so I’ve started another task over here where I’m re-writing the entire thing. I’ll send an email to Joe**** recommending that we use my new version, but it will take weeks of time to complete it and he’ll have to reorganize the entire second half of the quarter’s work schedule around it. I helped my supervisor at McDonald’s print the work schedules once, so I can help him do that.”

**** Joe was our manager, who came up from the developer ranks. He lead a team of 3 who wrote the library in just over a year. It was fundamental to our application, and everyone used it.

C: “I’m sure he’ll appreciate the advice. The library spits out log4j messages when you use it in application A. What do the logs say?”

A: (Silence)

C: “Can you open the logs?”

A: “So, here’s the code for the parser.” (Scrolls down, clicks) “This other class needs the method too. Oh! Ooooooh!! That’s probably where the problem is, that makes sense, doActionsXYZ calls it too.” (Opens a new file explorer window) “That’s over here.” (Click, scroll, double click, open, scroll, close, other file, opens three files, opens an email client, searches, reads 2 new messages, flips back to the IDE, opens 2 files, scrolls) “Here’s the method. Oh, oops, no, it’s doActionG. I added that last week. Looks like someone else changed it though.” (Pause, reading) “What did they do? That’s all wrong! Why didn’t they ask me about it if they needed to use it?” (Starts ranting about team communication)

C: (Too tired by this point to say please) “Can you just go back to the logs directory. Hold on, you had the window open, yeah, open that file.”

[Omitted scene where we detoured through several unsuccessful logging tool installations because Arthur didn’t like Notepad.]

A: (Scrolling) “There’s nothing here that’s important, why are we doing this? There aren’t any clear error messages here. I always make great error messages, this is just a bunch of class names and line numbers, it’s not helpful at all.”

C: “Stack traces can be informative to tell you where the application stopped working and provide clues on where to start looking. Hold on, scroll back up again, no, no, too far, yeah, down a bit. Where the stack trace starts. That line looks interesting: NullPointerException line 372. What’s on line 372 in the code?”

I’ll end the dialogue here because I think you’ve got the point and can probably see where it’s going. I’d like to complete the story with a happy ending, but instead Arthur eventually got so frustrated with my slow method of problem solving that he switched to a different task and I went back to my desk. I had become so intrigued with his problem that I worked on it a bit at the end of the day on my own. Remember that he was originally trying to do X, but went way off track at the start with W? There actually was a method, but it was called doActionEx. I found it after reading the (very detailed) wiki about the library, and then scanning through the JavaDoc. I was able to fully implement a basic prototype (which he’d still have to modify for his purpose but offered a good place to continue) in about 20 minutes, searching and reading time included. Our pair programming session took over an hour, and we never got close to a solution because he wouldn’t abandon W and we kept debugging a path that would never work.

Arthur the Intern: A Short Story Analysis

Over many interactions with other programmers, I’ve learned anti-patterns of new-ish programmers and how to recognize them (though certainly not like Arthur in that he exhibited so many of them at the same time!). Listing some of the story’s anti-patterns:

- ignoring the experience of others

- not truly listening to questions or answers from others

- inflating his own experience (or not understanding his own inexperience)

- misunderstanding the domain or main principles

- not understanding the problem

- making invalid assumptions (jumping to conclusions without searching for evidence to prove them)

- taking actions based on invalid assumptions

- looking for the hard implementation (not being lazy)

- not understanding a library or consulting the documentation

- assuming the problem is in the library and not in his chair

- an unnecessary sense of urgency for speed and action (thinking too much to stop and actually think)

- disjointed task focus (multitasking)

- not knowing how to use evidence finding tools (debuggers, logs, stack traces, etc)

- focusing on one part of the problem at a time as the only thing to solve instead of relating its fit to the bigger picture

- implementing the entire solution all at once instead of confirming he’s on the right track with smaller pieces and periodic checks

- copy / paste without understanding what the code is doing

- concluding a googled solution is the right answer because it contains similar keywords and an implementation with steps he (vaguely) recognizes

- pursuing the first branch he thought of to exhaustion before a sanity query: “am I on the right track?”

- getting mired too deep in details and not recognizing the implementation’s difficulty was a warning sign

- coding by chance (throwing something at the wall and hoping it sticks)

- impatience and frustration at the hard (but typical) programming headaches (giving up on the problem too soon)

Let’s detail a few of these anti-patterns that (IMHO) are the most common and disruptive:

Ignoring the experience of others and not understanding own inexperience

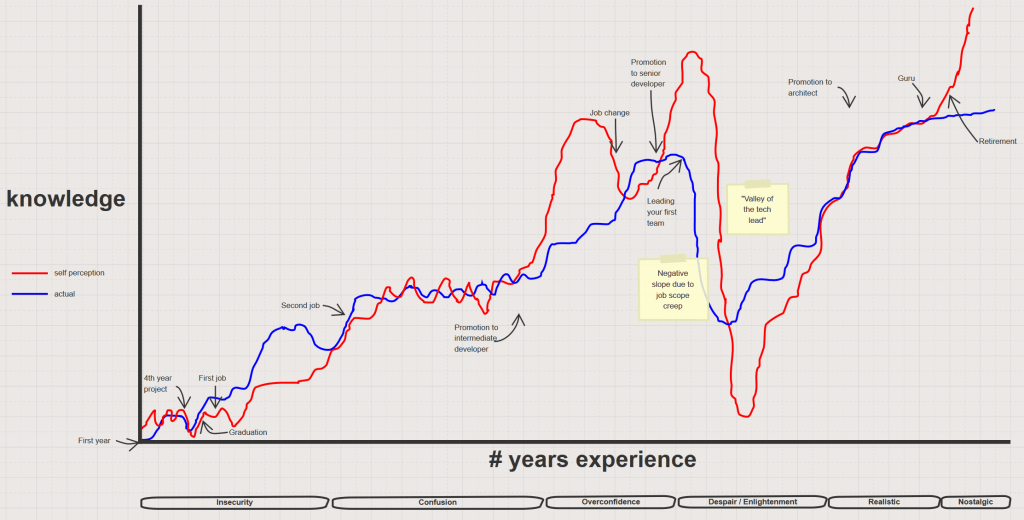

I’m amused by the paradox of the overconfidence effect: you don’t know what you don’t know. Some day I’d like to conduct a survey of developers at various stages in their careers and graph their evaluation of their own expertise vs their actual expertise. My intuition tells me it’ll look something like this:

I don’t know why developers find it difficult to take advice from others (and I’m counting myself in that statement as it continues to be one of my own recurring lessons learned). Maybe it’s a code ownership thing (stay away I wanna work on this interesting thing)? An introverted thing (leave me alone to work in peace)? A survival tactic in an ego-driven industry (gotta show my mad skillz to increase my rep)? In any case, learning from others is a way to quickly improve your own skills so you don’t have to repeat the mistakes they’ve made. I’ve heard this stated as “someone else will always know more kung fu than you and they can teach you some new moves if you ask and watch”. It can be humbling to be told you’re off track (especially in the moment), but wouldn’t you prefer that to spending hours and hours of wasted effort but end up in the same place in the end?

Disjointed task focus

Why do technical people admire multitasking so much and think that programmers who do it are efficient and fast? Sure, someone might be filling in compiling downtime by working on three other methods at the same time, but what are they doing when they switch, and is it actually the right thing? I have yet to meet a multi-tasker who was wasn’t actually just hacking a bunch of different things together hoping that one of them would stick, instead of using a deliberate approach. Yet they always look so busy, energetic, and impressive because others get lost following their whirlwind of activity. They must be super smart to think so quickly and get a ton of stuff done because of that velocity, right? It’s comparable to an energetic toddler running around hitting all the appliances and electronics in the house with a hammer. The toddler isn’t being an efficient handyman, he’s making trouble and someone else is going to have to clean up after him. Ask the toddler’s mother how she feels at the end of the day; a multi-tasker’s colleagues will feel the same drain.

Assuming the problem is in the library

A short and sweet response: it isn’t.

Depth-first problem solving

To me, Arthur’s biggest mistake was that he used the wrong problem solving algorithm. He was using a depth-first strategy, following one branch of thought all the way to the exhausted end before he would consider backing up the tree and trying a different path. That’s a big time commitment, and while DFS has its place, I don’t think problem solving is one of them. I use something closer to a breadth-first approach *****. When encountering a problem, I think of a few different solutions at a high level. I pick the most likely case (which can only be recognized with experience) and think of ways I can test that it’s viable. Then I research (using Google, Stack Overflow, or colleagues) and experiment (trying different libraries, exploring methods, making small changes to existing applications) to find evidence that the solution is still a candidate. Keeping what I learned in memory, I repeat this process with the other solutions. After one iteration, some of the branches can obviously be pruned because they’re unlikely to work or aren’t practical; others are more promising. This informs the next iteration where I repeat the investigation, going deeper into an implementation. Most of the time I’ve found a viable branch within a few iterations, and then start to focus on that solution. I spend my time thinking and testing, thinking and testing. This approach has served me well.

***** Geeky aside: actually my approach is probably closer to the A* search algorithm, but I digress :p

Conclusion

Problem solving is one of those aspects of computer programming that make it more artisan than logical. It requires creativity, experience, and a big old spoonful of humility. The awesome thing about technology is there are many ways to solve a problem. Each developer hones their craft in their own way, but there are still patterns that have proven successful and anti-patterns as warning buoys. Take a look at your own methods — do you exhibit some of the problem solving anti-patterns? Even us seasoned developers could use the occasional reminder… 😉